By Chris Chan

(This article expands on an earlier article, “Financial Accruals for Clinical Trials – A Primer”)

I’d love to report that since my first accruals article a decade ago, financially accruing for clinical trials and R&D expenses have gotten significantly easier and more efficient. I’d also love to be a handsome prince, but here we are. Although my scary appearance is a sunk cost, I can help make your financial accruals effort easier.

First, a recap of what accruals are and why they’re particularly challenging in the world of clinical trials. “Accruals” refers to accrual-basis accounting, which is the standard accounting methodology (and requirement) for most companies. Under this method, expenses are recognized when incurred, and revenues are recognized when earned. This is differentiated from cash-basis accounting, in which expenses and revenues are recognized when money changes hands. If I hire Barry Manilow to sing at my party in January and I pay him in February, his fee is recognized in January under accrual-basis but in February under cash-basis. Why is accrual-basis accounting so challenging when it comes to clinical trials? A very big reason is the sheer volume and complexity of all participating external players. In a typical trial, there are contract research organizations (CRO’s), investigator sites, central labs, specialty labs, clinical supply chain vendors, consultants, IRB’s, and many other partners. Each CRO could encompass multiple functions (project management, site monitoring, data management, safety tracking, biostatistics). Investigator sites can number in the many hundreds across multiple continents. Additionally, there could be a great number of specialty vendors and consultants. Since every one of these entities must be calculated and estimated for each accounting period, it’s easy to see why the effort is substantial. Biopharma companies try to meet this challenge with a combination of developing reasonable models, paying external vendors to assist, and hiring savvy and charismatic in-house expertise (like the author of this article).

Why hasn’t the clinical financial accruals effort gotten noticeably easier over time? Because clinical trials have not gotten any less complex, accounting has not gotten any less labyrinthian, and auditors have not become any more merciful.

After 2.5 decades of managing clinical/R&D financial accruals for a multitude of big and small biopharma companies, I have observed that by understanding some key concepts, the challenge of developing and implementing an accruals system becomes much more palatable.

Here are the seven important concepts for all financial accruals facilitators:

- Accrual vs. cash-basis accounting

- Simplicity

- SOX (The Sarbanes-Oxley Act)

- Perspective

- Auto-reversing entries

- Invoices

- NAAP

Without further ado, let’s dive into each of these concepts in greater depth.

Accrual vs. Cash Accounting

Suppose you earn $1,000 per week working for Ozzy Osbourne Industries, and suppose you get paid twice a month on the 1st and the 15th. After the first week of the month, if I asked you how much you earned so far this month, you probably wouldn’t say, “Zero, since I haven’t been paid yet.” You’d appropriately reply that you earned $1,000 despite not getting your paycheck yet. This is because when it comes to our salaries and wages, we understand the accruals concept.

In contrast, when it comes to estimating clinical trial expenses, many folks naturally think on a cash basis. Here are a couple of oft-observed examples: (a) when a clinical manager estimates expenses to be $1M because a $1M payment has just been sent to the CRO – even though the $1M is an upfront payment and the CRO has performed no work to date; (b) when the same manager estimates zero expenses because the next milestone payment isn’t expected for several months – even though the CRO has been consistently performing work during the period.

This misalignment is a very common reason behind inaccurate accruals and budgeting. Fortunately, the remedy is quite simple: training and more training, socializing and more socializing. When I worked for a large well-known biotech (don’t want to mention names, but let’s say it rhymes with Benentech), the R&D Finance team partnered with key clinical leaders and put together an accruals training roadshow for all personnel within the Clinical Operations organization. The result was an almost immediate significant improvement in budgeting accuracy and accruals precision. Additionally, understanding of budget vs. spend status reports increased dramatically.

The punchline: enhancing how well all relevant personnel comprehend the accruals concept will immediately improve the efficiency and accuracy of your accruals.

Simplicity and Practicality

When it comes to accruals, you can easily fall down the rabbit hole of over-complexity. After all, we need to be as accurate as possible, right? However, it is very important to keep the following notion in mind: accruals are estimates. By their very nature, it’s virtually impossible to achieve maximum accuracy. We simply strive to get as close as we reasonably and practically can. In many ways, accruals is as much “forecast” as it is “accounting”.

As such, when it comes to deciding on what accrual methodologies and modeling to use, the rule of thumb is to make your methodologies as simple as possible.

But the key question is – what is “possible”? This depends on (a) the size and scope of your company’s overall activities; (b) the human and technological resources available; (c) the risk tolerance of your CEO/CFO/corporate controller, and (d) the personalities of your financial auditors.

It is a fact that different biopharma companies use a variety of differing methodologies. Some accrue using a simplistic straight-line methodology (simply dividing the contract amount by estimated number of months duration and accruing equal amounts every period). Others build models that accrue based on predetermined cost drivers such as enrolled patients, site initiations and monitoring visits. Some just email their vendors every period and ask for estimated amounts.

Again, your company’s particular attributes will determine the appropriateness of methodology. The straight-line method might be acceptable for a large company with hundreds or thousands of contracts that will average out, but less so for a small company with a small number of early-stage trials run by one or two CRO’s. Similarly, a large company with numerous vendors will find it impractical to solicit vendor updates every period.

But again, using the simplest, most feasible option possible for your acceptable risk tolerance is key. If you create accruals models, choose one with the fewest and most easily obtainable cost drivers. It would be easy to update your accruals models if patient enrollment was the only cost driver, but much more onerous if you need to obtain enrolled patients, initiated sites, monitoring visits, case report forms cleaned, and so on. If possible, use standing reports already being circulated by your clinical partners as your data input source. This way, your clinical partners aren’t burdened with doing additional work for you every period, and you don’t have to wait so long for the data.

In summary, determine the most appropriate level of complexity and effort for your company and opt for the simplest methodologies possible. This will avoid unnecessary burden for everyone involved and make your workdays much more pleasant.

SOX (The Sarbanes Oxley Act)

Curtain opens to a somber orchestra tune in andante pianissimo. Two figures sit across from one another gazing intensely at respective laptop screens:

Auditor: I’ve verified your numbers are correct. Now show me evidence that you properly performed all required checks and verifications.

Accountant: At the bottom of every page, you can see my signature verifying that I did all necessary checks.

Auditor: How do I know you didn’t just sign every page without actual review?

Accountant: Swear to God and hope to die?

Auditor: Not good enough.

Accountant: Stick a needle in my eye?

Auditor: I need to see verification tick marks on each section.

Accountant: Do verification smudges count?

Auditor: Nope. Also, show me evidence that your reviews were reviewed by another person.

Accountant: Right there! You can see the accounting manager’s signature verifying that he checked my checks.

Auditor: How do I know he didn’t just pre-populate his signatures prior to your review?

Accountant: He was in a coma until yesterday. Here’s a doctor’s note.

Sadly, the preceding scene is based on real-life events that commonly occurred since the start of this century.

After the financial scandals of Enron and WorldCom, the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002. Two major ramifications of this act: (a) it requires senior corporate executives to certify — with personal liability — that their company’s financial statements are accurate; and (b) it requires that publicly-traded companies implement systems of internal controls that check for misstatements and errors along the financial reporting process. Therefore, under SOX, not only are the numbers audited for accuracy, but the control processes themselves are assessed, tested, and audited on an ongoing basis.

What does this have to do with accruals? Since the accruals process falls under SOX controls, every step of the process is documented in a detailed narrative, and every subsequent performance of said process must be documented, verified, and scrutinized. As such, it is important to make the documented steps as straightforward and reasonable as you can. Fewer mandatory steps specified is preferable. Increased flexibility is better.

Let’s suppose that you’ve implemented a new complex process and you decide to have three people review the work (say, the accounting manager, the assistant controller, and the controller). However, you’ve also determined that while three reviews would provide comfort, two reviews are adequate. In this situation, go ahead and perform three levels of review, but only specify two reviews in the SOX documentation. This way, you have the option of performing two or three reviews and won’t be found deficient if you only perform two. Just as overly complicated clinical research standard operating procedures (SOPs) invite errors and FDA sanctions, complicated expense accruals procedures can lead to SOX deficiencies. As such, keep your documented accrual processes and models as straightforward and easy to adhere to as possible.

Perspective

As mentioned previously, accruals are estimates.

If your goal is to determine how many grains of sand are on Waikiki beach every month, you can hire a vast army of sand counters to count every grain. Alternatively, you can ask a smart geologist to create a model that will generate reasonable estimates.

When it comes to accruals, many study sponsors do the equivalent of counting grains of sand. They contact dozens of different service providers — and even more sites — every month to provide data estimates. They build complex accrual models that call for multiple inputs that require many hours to collect and many more hours to process. Be a smart geologist, not a sand counter.

Additionally, when it comes to vendor-generated data, the principle of garbage-in-garbage-out can come into play. In one of my previous companies, a well-known CRO provided data that we used for monthly accruals. After we noted some weird discrepancies with the data, the CRO admitted they were just guessing at a lot of them. When you ask a service provider to do something impractical for them, do not expect excellent results.

The solution is to maintain a reasonable perspective. Avoid excess precision by determining when incremental precision isn’t justified by the burdensome means to achieve it (the 80/20 rule). Do not create sophisticatedly complex accrual models that look great on paper or monitor screen but are too oppressive to update.

If your company’s leadership is reluctant to adopt methods of estimation that seem risky, you can demonstrate that the risk level is acceptable. For example, you can convince them that a proposed new methodology is feasible by comparing what accrued expenses would have looked like versus actual expenses over the past 2-3 years and demonstrating they are not materially different. If the analysis shows significant difference, you can incrementally increase the complexity of your proposed model until you find one that’s feasible.

Auto-Reversing Entries

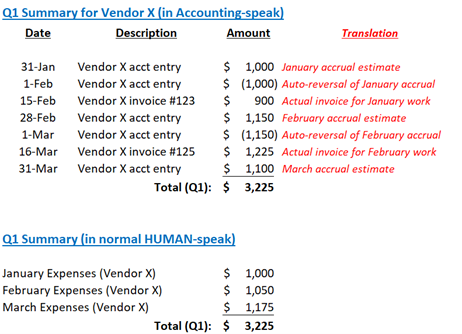

Auto-reversing entries are a magical tool used by your accountants that play a very important role in the accruals process, and understanding this concept is essential.

First, what is an auto-reversing entry? Basically, it is a way to ensure that accrued expenses and related invoices are “charged” to the appropriate period. An invoice for January work that arrives in February should not count as a February expense.

Here’s how it works:

- When an accrual estimate is input into the accounting system, it’s set up as an “automatically reversing entry.”

- Whatever the amount of the accrual estimate is in one month, the accounting system will automatically generate the exact reverse amount for that account at the beginning of the following month. Ergo, you will start out the following month with that negative amount.

- When the invoice comes in during that following month, the negative reversal amount and the invoice offset.

For example, if you accrue $1,000 for a CRO fee in January and set it up as an auto-reversing entry, there will be a negative ($1,000) at the beginning of February. Then when the $1,000 invoice comes in during February, the negative ($1,000) offsets the $1,000 invoice. Net effect: $1,000 expense hit in January; $0 expense hit in February.

What happens if your accrual estimate turns out to be imprecise? Let’s suppose you accrue $1,000 but the actual invoice in February is $1,200. In that case, after the negative ($1,000) offsets the invoice, there will be a positive $200 balance. That difference will result in a February “correction expense”. Similarly, if the actual invoice is $900, then the February balance would be negative ($100) and that would result in a $100 “correction credit” in February.

Figure 1: Example of Accounting Summary with auto-reversing entries

Not only do auto-reversing entries ensure that expenses hit the appropriate time period, they also provide a signal confirming the accuracy of your original accrual and effectiveness of your accrual methodology. Additionally, they reinforce the concept of accrual-basis accounting and assure everyone that inexact estimates will be corrected.

Invoices

Understanding invoices within the context of the accruals process is crucial. As alluded to previously, there is often confusion associated with timing of invoice receipt: an invoice received in February isn’t a February expense if the associated work was performed in January. Furthermore, invoice amounts are still a commonly used proxy for estimating expenses. For instance, a frequently used method of estimating expenses for a given period would be to contact the vendor and ask, “What’s the amount of your next invoice?” Unfortunately, invoices are often not an accurate reflection of a period’s activities. Easy examples of this are upfront and milestone payments. If you accrue the full amount of a $1 million upfront payment before any work is performed, you will be overstating expenses by $1 million.

Additionally, something that frequently confuses those who contribute accruals estimates is not knowing the exact stage of the invoice within the financial system “conveyer belt”. Has the invoice been accounted for as an expense? Should I factor in the invoice amount when I provide my accrual estimate? If the invoice has been received, can I assume it’s been accounted for? What if it’s still being routed for approval? What if it’s been approved but won’t be paid until the next payment run two weeks from now?

Ultimately, the business partners who provide accrual estimates need to know whether the Accounting department has expensed (or “posted”) the invoice amount in order to provide a proper estimate. To ensure this, there must be a workable system that provides posted invoice data to all partners in a timely and easy-to-use manner, and they must remember to use it. This necessity is a significant challenge to say the least – especially when many business partners still struggle with the accruals concept!

My solution to this challenge is elegantly simple: remove the “invoice” factor for all your business partners. In other words, when estimating their accruals business partners should ignore the existence of invoices altogether. They should simply provide a total cost estimate of all activities performed during the period. After Accounting personnel receive these accrual estimates, the accountants will then offset the gross estimates with any relevant posted invoices.

Bottom line: understanding the characteristics and context of invoices as they pertain to every step of the accruals process is crucial if you want to generate proper accruals.

NAAP

Just as our esteemed Clinical and Manufacturing colleagues follow GCP and GMP guidelines, professional accountants are guided by GAAP, or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

When it comes to clinical trials accruals, the reigning guideline is NAAP, or No Accepted Accruals Practices.

That’s right – accruals in the biopharmaceutical industry are a free-for-all. Every company comes up with their own methodologies. Some companies develop fancy models with esoteric cost drivers. Other opt for a simple straight-line method. Still another might do a twist by immediately expensing 30% of each contract and straight-lining the remaining 70% (as was once done by a venerable biopharma that rhymes with Mamgen…).

After giving financial accruals presentations and workshops, I’m frequently approached by attendees who sheepishly share their respective accrual methodologies. Although the processes they created through trial-and-error seem to work OK, they suspect those processes are substandard. My typical response: (a) there is no standard…so how could your methods be substandard? If they work, they’re adequate. And (b) like shingles, accruals are painful by nature; your goal is to tweak your processes to be as efficient and least painful as possible.

Rather than regarding NAAP as a frustrating situation, use it to your advantage by designing your accruals processes and models in a way that most feasibly fits your company:

- Determine your company’s level of risk tolerance by looping in your company’s C-suite leaders into the decision process. Present the pros and cons of different process options and underscore that degree of precision correlates to increased or decreased resource, effort, and timing.

Generate and implement the simplest, most reasonable accrual methodologies for your determined level of risk tolerance.

Ensure that your company’s leadership, external auditors, and service providers understand your established process; keep them apprised of any issues, revisions, and updates.

By understanding and accepting NAAP, you can harness its intrinsic flexibility and turn it into a positive.

Conclusion

Although financial accruals can be a challenging and even painful endeavor, one can make the effort go from profoundly torturesome to mildly achy by focusing on the afore-discussed concepts. By incorporating at least some of these elements and educating your inter-departmental colleagues as well, I am confident you will increase the efficiency and proficiency of your process. Once again, the seven concepts are:

- Accrual vs. cash-basis accounting

- Simplicity

- SOX

- Perspective

- Auto-reversing entries

- Invoices

- NAAP

Therefore, when you contemplate and plan your financial accruals process, always remember ASSPAIN and this article.

As the wise philosopher and imperial accountant Confusion once said: the journey of a thousand financial statements begins with a single thoughtful auto-reversing entry.

Reference

- “Financial Accruals for Clinical Trials – A Primer,” Christopher Chan, Journal of Clinical Research Best Practices,” September 2013, https://www.magiworld.org/resources/journal/1435_Accruals.pdf

Author

Chris Chan is Vice President, Head of FP&A at IGM Biosciences. Contact him at cchan7556@yahoo.com